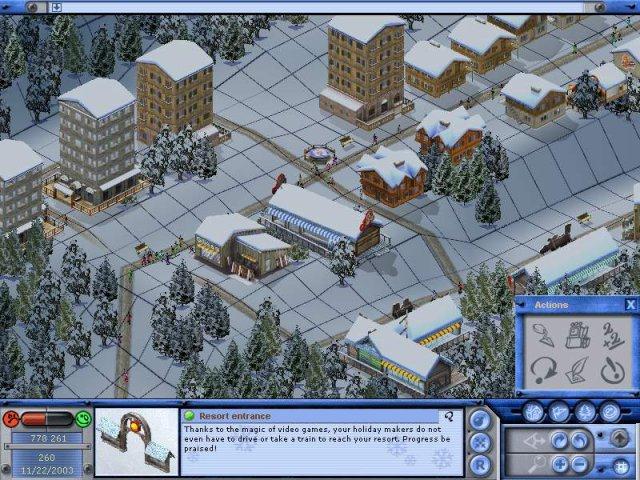

Ski Park Manager 2007 Torrent

Ski park manager 2003 partie 6. This feature is not available right now. Please try again later. Movie Torrents. View all TV Torrents. View all ExtraTorrents Shadow: Shadow's torrents (total 1349 torrents. Pussyfuck erotic drawings auntie abused encyclopedia+homeopathica 5.25 Hd porn bright hindi ski park manager bethe adobe illustratorlynda power sp the 100 SO1E01 to xart Unbelievable Sunenlo 1.5.

Millions of gallons of untreated sewage were dumped into Quincy Bay during this past week’s storm, exposing limitations of the $115 million Nut Island facility as well as flaws in an aging network of underground sewer lines that channel waste from 21 communities to Quincy. Kelly As a nor’easter pounded the city for a third day last week, rain water and sewage surged into the Nut Island Headworks plant at a record 16 million gallons per hour. The rank river was rising fast. An alarm sounded. Sewage was on the verge of spilling into the streets of Houghs Neck from a backed-up pumping station.

At the plant, a worker lifted a metal hatch and crouched down with a ruler to see how close the foul water was to spilling over – 3 inches, 2 inches, 1 inch. Recounting the incident, workers involved said the decision March 15 to pour millions of gallons of untreated wastewater into Quincy Bay was clear-cut – a lesser evil for public health; a saving grace for the costly plant.

Criticism that has followed, they said, only reinforces the progress made from days when raw sewage washed ashore with regularity and when critics here gave “sewer tours” of the dirtiest harbor in the United States. Still, the sewage bypass – the plant’s first since an electrical failure in 2005 – exposed limitations of the 12-year-old, $115 million facility, built in 1998, as well as vast flaws in an aging network of underground sewer lines that channel waste from 21 communities to Quincy.

The Massachusetts Water Resources Authority has spent $5.3 billion on wastewater infrastructure since its creation in 1984. In the past decade, it has made $261 million available through grants and low-interest loans to cities and towns to replace pipes that are, in some cases, 100 years old. Yet when it rains, stormwater infiltrates sewer lines in high volume, at times straining the Nut Island plant, which has a daily capacity of 400 million gallons. City Councilor Daniel Raymondi, whose ward is down the coast from the plant, railed against the MWRA, saying the agency should reimburse the city for any damage to the bay. “It’s beyond the question of if they had a right,” Raymondi said.

“If they damaged the bay or if homes were damaged. They ought to be held accountable.” In a letter to the U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency, MWRA CEO Michael J. Hornbrook said 5 million to 10 million gallons were sent into the bay over a one-hour period – down from an initial estimate of 15 million. He said there was “no feasible alternative” given that 8 to 11 inches of rain fell during the nor’easter, which he called the worst two-day storm here since Hurricane Diane in 1955. Water samples tested Tuesday show elevated bacteria counts in three of four locations. The highest count was near the plant: fecal coliform was measured at 1,200 percent above acceptable standards.

“As a result of flow to the harbor from direct runoff, stormwater and rivers, it is difficult to say with any confidence whether the short-term bypasses were the source of the bacteria,” Hornbrook wrote. In severe storms, groundwater rises above sewer lines, flushing into the system through cracks that are caused by time and tree roots.

On streets where flooding is particularly bad, rainwater gushes through holes in manhole covers, which, in extreme cases, are pushed off entirely by floodwaters. In turn, sewage can seep from the pipes into the groundwater, eventually running off toward the ocean or other waterways. “In storms like this one, it’s all dirty water,” said Frederick Laskey, executive director of the MWRA. More than 5,000 miles of sewer pipe runs beneath the 43 communities in MWRA’s system.

Replacing damaged sections carries is hugely expensive. “The environmentalists want to be at zero-tolerance,” said Brian McNamee, a city councilor who is finance director of a sewer system in Essex County. Copilot usb driver windows 10.

“But you don’t want that bill.” “It’s theoretically possible to build a system that could withstand a 100-year rain event,” McNamee said, speaking in his capacity as a city councilor. “It’s just not cost-effective.” An MWRA program has helped communities modernize sewer infrastructure through grants and loans. Quincy spent $9.4 million in the past seven years, Braintree spent $2.5 million, and Weymouth spent $4.5 million, according to the authority’s figures. Michael Coffey, business manager for the Quincy’s public works department, said one concern is seawater infiltration, which occurs through manholes and pipe separations near the city’s coastal marshes. “What it really means is our sewer bill from the MRWA is 30 to 40 percent higher,” Coffey said, estimating the percentage of infiltration that needlessly gets treated as wastewater. As the inflow at the Nut Island Headworks receded this week, MWRA officials touring the facility with a reporter said a public-health disaster was averted by sending the sewer water into the bay instead of letting it back up into residents’ homes.

Likewise, they said “odor-control” and other equipment in the plant’s basement was saved from a spillover flood. Such an event would decommission a facility designed to handle all but the most extreme volumes of waste water. Jack Walsh, a member of the authority’s board of directors, said bypasses in the 1980s were ordered “every time we got a half-inch of rain.” James MacPherson, who operated the plant for 22 years, topping his father’s 15 years in charge, said that sludge, once emptied into the bay without a second thought, is now piped to New England Fertilizer to make fertilizer pellets. “We used to dump (waste) twice a day right there,” MacPherson said, gesturing toward the ocean. “Once at high tide, once at low tide.” The Massachusetts state Department of Environmental Protection is reviewing the bypasses.

“It appears this was the best alternative to make sure the facility didn’t overflow and the sewage didn’t back up into people’s homes and businesses,” spokesman Ed Coletta said. Patriot Ledger writer John P. Kelly is at jkelly@ledger.com.

Ski Park Manager 2007 Torrent Online

Over 100 years of pollution, cleanup 1904: A sewer pipe running into Quincy Bay is completed. Raw sewage would continue to move through the pipes and into the water, unabated, for 48 years. May 1908: Wollaston Beach “opens” with the completion of Metropolitan Boulevard from Atlantic Street to Fenno Street. 1945: At the urging of Quincy residents, the Legislature OKs $4.5 million in spending for a sewage treatment plant at Nut Island. 1952: The Nut Island sewage treatment plant is completed, removing about half the solids from up to 300 million gallons of sewage sent each day.

1978: Federal environmental officials block the Metropolitan District Commission’s plan to expand the Nut Island plant. 1982: City solicitor William Golden spots human feces on Wollaston Beach, spurring him to action. Quincy sues the MDC and other state agencies for sewage discharges from Nut Island – leading to a court- ordered, multibillion dollar harbor cleanup and the creation of the Massachusetts Water Resources.

1988: Presidential candidate George H.W. Bush comes to Massachusetts to criticize his opponent, Gov. Michael Dukakis, and “the filthiest harbor in America.” 1989: James Sheets is elected Quincy mayor, with a campaign heavy on MWRA bashing. Clam diggers are banned from the Wollaston area because of pollution. 1995: After three years of delays, the Nut Island sewage tunnel is completed. 1996: Overwhelmed by melting snow and heavy rain, wastewater treatment plants are spilling more than 20 million gallons per day of partially treated sewage into South Shore waterways, threatening beaches and shellfish beds.

1997: After spending $3.7 billion, the MWRA starts discharging clear wastewater into Boston Harbor with the opening of a new regional sewage-treatment plant on Deer Island. October 1998: The Nut Island sewage treatment plant is shut down, although it remains a sewage screening facility. Its 17 acres open a year later as a park.

2000: Wollaston clam beds are deemed clean enough for diggers to return. 2003: Quincy begins a $12 million project to repair crumbling sewer lines. 2005: After an electrical failure, 25 million gallons of untreated wastewater is dumped into Quincy Bay. Summer 2007: Wollaston Beach is deemed “swimmable” 90 percent of the time. Sources: Patriot Ledger, Mass.

Ski Park Manager 2007 Torrent Download

Water Resources.